Henry Morgan’s privateering exploits had turned to full on piracy by the time he attacked Maracaibo and, especially, Panama City. Still, he enjoyed the support of the island’s population and leadership, and the money he brought to the colony facilitated its transformation into one of England’s wealthiest colonies.

Transcript

By 1669, Henry Morgan’s buccaneering exploits had yielded hundreds of thousands of pounds sterling worth of loot, most of which had been spent on drunken rampages in Jamaica. This influx of money had enabled the development of the colony in many ways, and made him extremely popular with its residents, as well as its leadership. Governor Thomas Modiford was his close friend and ally, and Charles II, who also got a cut of the loot, indirectly encouraged him while officially reprimanding him in response to Spanish complaints.

Introduction

Hey everyone! Sorry for the delay, but if you follow me on social media, you’ll know that this is because I just got done visiting a few places which are extremely relevant to our podcast, specifically, Providence Island and Barbados, with a stop in Cartagena. And, while I was there I created some little bits of content which I’ll be posting to Facebook and twitter over the next few weeks, so you get to see exactly where some of this stuff happened. So if that interests you, please head over!

Also, if you’ve been wondering when we’ll be back in mainland North America, the answer is next episode! As we start the history of Carolina. But that also doesn’t mean we’re going to fully leave our Caribbean stuff behind, as you’ll see.

And now, on with the story.

By 1669, Henry Morgan was easily the most famous pirate in at least the English speaking world. His exploits had been more than just borderline illegal. England was officially at peace with Spain for the first time in a century, and it was at war with France, which had emerged as England’s leading competitor in the Caribbean. Spain, thanks in large part to privateering efforts, was no longer strong enough to support its own empire, much less challenge other countries’ attempts to settle the area. Plenty of its possessions were sparsely inhabited and its strength was clearly waning. And meanwhile, France had pulled the Dutch into a second war with England in an attempt to weaken its position in the area. French ships sailed into English ports and refused to salute. French governors paid Carib tribes to slaughter English colonists. And France had earned a reputation among people in Barbados and the Leewards for being the most aggressive and hostile of countries toward the English.

Spain and England had also signed a peace agreement in which Spain conceded England’s right to own Caribbean colonies.

Despite all of this, though, Morgan had sought privateering commissions from Modiford to plunder Spanish cities, citing the most dubious of threats. And Modiford had given them, both because Spain was still the number one enemy in the hearts of many English people, and because Spanish colonies did still send plenty of gold and other valuables back to the mother country. Charles II slapped both on the wrist for these exploits, but he also knighted them both, and he gave them both titles. Modiford remained governor, and Morgan was named lieutenant general of Jamaica and admiral of its fleet. Charles gave him well over 4,000 pounds, as well as one of the nicest ships New England had ever built, which he proceeded to immediately and accidentally sink.

At this point, piracy was so far removed from the Puritan religious motives which had once defined people like Drake, that French and even some Irish Catholics had joined in English attacks on the Spanish. Of course, there were some Irish pirates who made their home in Havana and specifically targeted the English, but the point is, the religious lines had been blurred. It was, first and foremost, about the lifestyle and the money, and this was true for everyone from the average pirate to Morgan and Modiford, to the king, himself. These actions did indirectly protect Jamaica from French attack, though, because a privateering hub that was fundamentally English meant that there were a fair number of armed ships available to defend the island at any given time. Beyond that passive defense, though, pirates did little for the cause of England’s war efforts, the brunt of which were born by Barbados.

And for Morgan in particular, success had begat success, and as his reputation grew, so did his fleet, because aspiring pirates from all nations went out of their way to serve with him. This even included France, though there was certainly more tension in those cases. He had become a hero in the eyes of the English, both in Jamaica and England itself. As his situation had improved, he’d also immersed himself more and more in the excesses of the pirate life, and he attempted raids with greater and greater potential rewards.

In 1669, his target was Maracaibo, in modern Venezuela. For the most part, the story of this raid is pretty similar to the ones we’ve discussed so far. They approached in canoes and took the town’s two forts without much trouble. And soon they approached an empty and deserted town whose inhabitants had all fled into the woods.

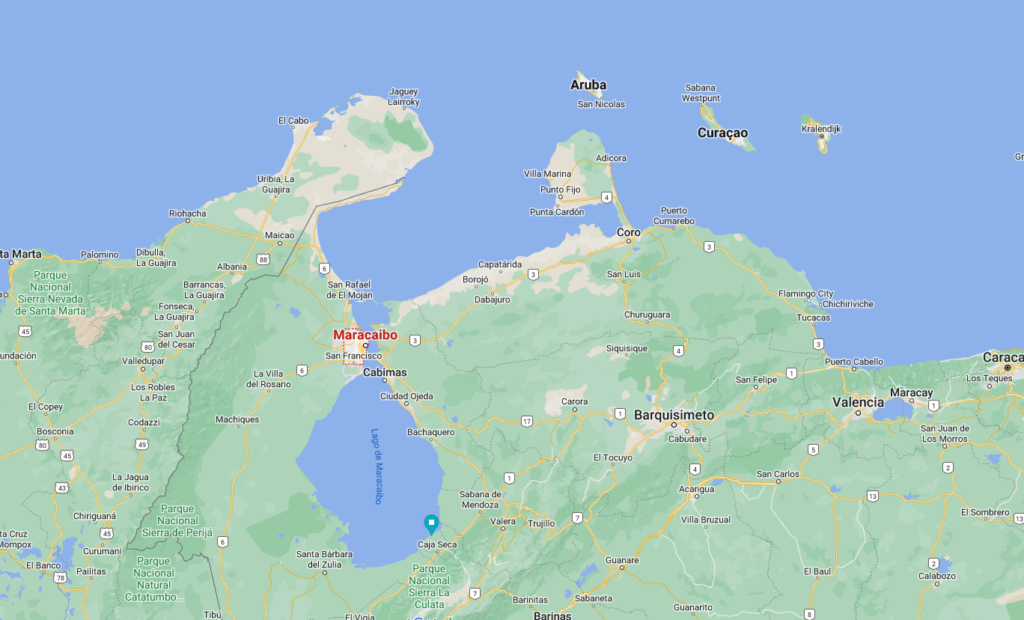

They spent three weeks tracking people down and torturing them until they either died or gave up their possessions, and then they went to Gibraltar. I’ve posted a picture of this map to twitter and facebook, but Gibraltar was on the same lake as Maracaibo, just further inland. The lake is connected to the Caribbean Sea via a small strait, so you can get into the lake using ships, and then sail around it. And in Gibraltar it was more of the same. On arrival, they found an empty town whose inhabitants had all fled. Actually, almost all, because they did find one mentally disabled man who hadn’t managed to get out in time. And they caught him, and put him to the rack. He screamed “do not torture me anymore, but come with me and I will show you my goods and riches,” so Morgan and his men let him down, and the man guided them to a rundown hovel with a couple of earthenware dishes. And there, he showed them where he had buried the three pieces of eight he owned. Disgusted, they tried to get more information out of him, and in the course of this interrogation he claimed to be the brother of the governor of Maracaibo, so they tortured him to death using the rack while touching burning palm leaves to his face, and then they dumped his body in the woods. There are a lot of individual torture stories in the accounts of Morgan’s adventures, but that one stuck out to me.

As they continued their search, they found a couple other poorer people, including a peasant who they hanged in front of his daughters, and a slave who they promised a share of the plunder and liberty in Jamaica in exchange for joining them. The slave agreed, and guided them to a group of Spanish people who they took prisoner. Then, to ensure the slave couldn’t change his mind, they ordered him to kill some of the prisoners while the others watched, and he did. And then, again, the pirates spent a few weeks finding, torturing, killing, raping, and pillaging. They returned to Maracaibo with a boat full of prisoners, and ransomed both Maracaibo and Gibraltar, demanding more money to stop them from burning the towns to the ground, but it was then that things took a turn for the unexpected.

In Maracaibo, an old man told them that a Spanish naval fleet was waiting at the entrance to the lake, which meant that Morgan’s was trapped. This fleet had been sent from Spain by the king to deal with Morgan after Charles II had repeatedly failed to stop his activities. The Spanish had three ships, and while Morgan had more, most were mere boats in comparison. Even Morgan’s own ship, the one he’d stolen from the French, had half the number of guns as just one of the Spanish ones.

So Morgan was not only trapped, he was hopelessly overpowered. Escape was impossible. Fighting back was impossible.

The only advantage he really had was hostages, which he might be able to use to negotiate, or at least buy time. In fact, the residents of Maracaibo and Gibraltar had already paid the ransom for these people, but Morgan had kept them anyway when he heard about the Spanish fleet.

So he opened the negotiations. He would burn Maracaibo to the ground if he weren’t allowed to leave. The Spanish admiral, Don Alonso, responded that if Morgan didn’t free every single person and return all the treasure, he would kill every single one of Morgan’s pirates. And Morgan countered that, in exchange for free passage he’d free all Spanish and Portuguese prisoners, along with half the slaves, and he would leave without doing further damage to the town. Alonso told Morgan those terms were so ridiculous that it’d be dishonorable for him to take them. He gave Morgan two days to surrender before being attacked and hunted down.

And that was enough for Morgan. His men spent the two days gathering pitch, tar and brimstone from Maracaibo, as well as other flammable things. He found African drums and painted them black to look like cannons, and then moved all women, gold and merchandise into different ships. One of the Maracaibo slaves saw Morgan doing this and rushed to tell Don Alonso that Morgan was making a fireship, but Alonso blew him off saying he couldn’t imagine that the pirates had either the intelligence or the tools to do something like that.

The next day as the sun rose, Morgan and Alonso’s fleets faced each other, and each sailed slowly forward. At the head of Morgan’s ship was the ship Morgan had spent two days preparing, and that one started to inch away from the rest of Morgan’s fleet. As it reached Alonso’s ship, it burst into flames and took the Spanish one with it. By the time Alonso realized that the slave had been right, it was too late. Fire had spread, and his men either jumped in the water and swam to shore, or were trapped inside the burning vessel. And with that, the Spanish fleet collapsed. The second one rushed toward the fort to reinforce it, and its sailors then destroyed their own ship to prevent it being captured by Morgan. Morgan actually did capture the last one. Surviving Spanish sailors jumped into the lake and swam to the fort, prepared to fight to the death rather than be taken prisoner.

Morgan was still trapped, though. He couldn’t sail his fleet by the fort without it being destroyed. He still had his prisoners, and threatened to hang them from the sides of his ships if he wasn’t granted free passage, but Alonso refused. It looked like Morgan would have to attack the fort.

So, in plain sight of the Spanish, he sent rowboats full of pirates to the fort, and then he waited. Alonso watched, anticipating an attack, and moved all of the fort’s weapons to the place that the pirates would most likely try to scale the walls. All the cannons, all the muskets, now faced away from Morgan’s fleet, and toward the land. And with all the weapons moved, Morgan waited for nightfall and quietly slipped out of the harbor. The rowboats full of pirates hadn’t actually emptied themselves out at the shore. They’d simply hidden their human cargo for the return ship to trick the Spanish. And Morgan was free, now with a Spanish naval vessel at the head of his fleet.

Alonso had had an overwhelming advantage, and every opportunity to win. If Alonso had listened to the slave, Morgan wouldn’t have won. If Alonso had accepted hostage deaths and simply exterminated the pirates without negotiating, Morgan wouldn’t have won. If Alonso had kept even a couple of the fort’s cannons facing the entrance to the bay he was supposed to protect, Morgan wouldn’t have won. And yet, Morgan not only survived, but profited from Alonso’s efforts and sailed out of Lake Maracaibo stronger than he’d ever been.

Morgan’s fleet sailed to Jamaica to wild celebration. They spent the money, and Morgan planned what would be his biggest venture ever. For this, he recruited every pirate he could find in either Jamaica or Tortuga, the French-run pirate base off Hispaniola. This, I must emphasize, meant that he had a huge portion of French sailors in his fleet, who wanted a share of the spoils, but didn’t particularly like the English pirates or their leader. Fully assembled, Morgan’s fleet stocked up on corn and pigs with a minor raid near Cartagena, and after that was divided they sailed for Providence Island.

They retook Providence from the Spanish in a way that was almost bloodless. After landing and approaching the island’s town, Morgan gave an ultimatum ordering the Spanish to surrender or be slaughtered. In response, the Spanish governor agreed to surrender, but asked for a completely fake battle beforehand, so he could preserve his reputation. Morgan agreed, stipulating that if one pirate was so much as injured, he’d not just kill but torture all the Spanish, and the governor accepted these terms.

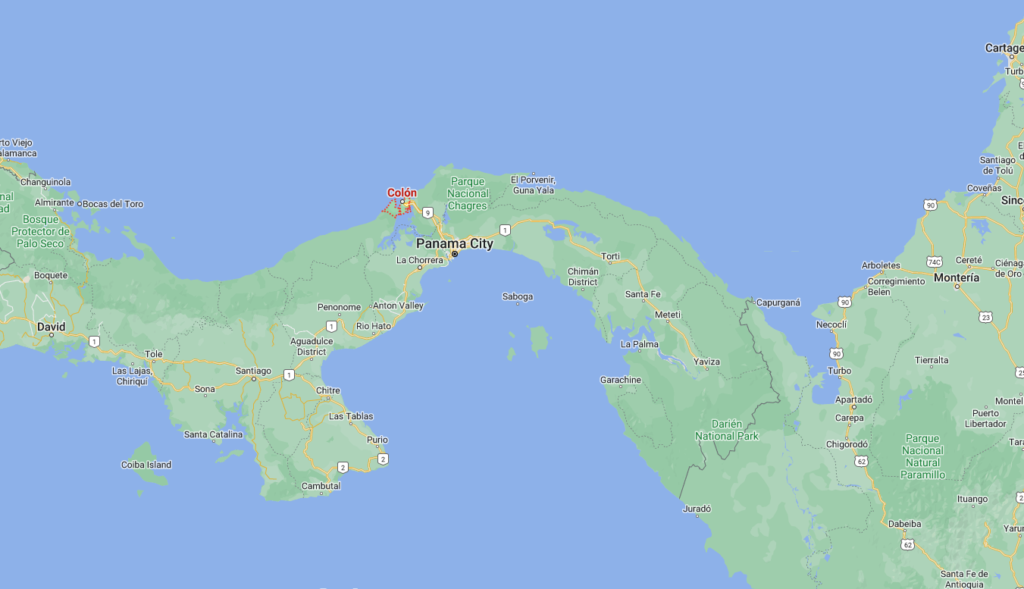

The two sides spent a couple hours shooting blanks at each other, the Spanish surrendered, and Morgan took them prisoner. He would drop them off at Porto Bello on the way to his next destination, Panama City. Much like Cartagena was the storehouse and port for all the gold from what’s now Colombia and the surrounding countries, Panama was the port for all the gold shipped from Peru. If anything, it was even more extravagant, and unlike Cartagena, it wasn’t surrounded by a wall. This was because it was so far away from the Caribbean coast. Panama City was on Panama’s Pacific coast, instead, and that provided its protection from pirates. Morgan’s men would have to land at a Caribbean town in the area, and make their way across Panama by some combination of river and land.

As their landing point, Morgan chose the Fort of Chagres, near modern Colon. He stayed in Providence while he sent his second in command to take it while he stayed in Providence. In Providence, Morgan recruited some guides for their trek, and also dismantled the island’s defenses so the Spanish couldn’t retake it as easily. This worked, and Providence remained in English hands until Queen Victoria gave it to Colombia. He left just one fort standing, the original Fort Warwick, built by the original English settlers four decades earlier. But he threw all its ordinance into the sea, so no one but him could find it again.

Meanwhile, when Morgan’s men arrived in Chagres, they found the Spanish prepared for an attack. Cartagena knew Morgan was planning something thanks to his food-gathering raid, and had warned potential targets. After a vicious battle, Morgan’s fleet had lost 170 men, over half of its people, but the Spanish fared worse. Only 30 of the original 314 Spanish survived, and 20 of them were wounded. And when Morgan received news of the victory, he sailed from Providence with the rest of his fleet.

On August 18, 1670, Morgan and 1,200 men rowed in 32 canoes from Chagres toward Panama City. They didn’t get very far, and they couldn’t find as much food as they anticipated. The food they’d previously plundered had already been eaten in the weeks preparing for the attack, and it wouldn’t have fit in the canoes, anyway. They had always supplemented with food from the area they were plundering, and yet there was none. The next day, the majority had to leave their canoes behind, too, because the river was too dry. And it became clear that the Spanish had stripped the land of food to slow the pirates’ march. It was only after eight days walking through the jungle with virtually nothing to eat, followed by spies and ambushed multiple times, that they arrived at Panama City. There, they found cattle, horses and donkeys, which they slaughtered and ate. And then, they approached the city. The governor was ready for them, though, and however Morgan’s men tried to approach, they met armed resistance. And the Spanish fought hard. So did the pirates, though, not least because they were now stranded eight days from their ships. This meant that for both sides, the options were to win or die, and that should give you some sort of an idea of how vicious the battle was.

Ultimately, it was the Spanish who were forced to retreat and regroup. The pirates found stragglers and shot them. They found priests and shot them. And they finally found someone who gave up some information about the city’s defenses, but even though he plotted what seemed to be the safest entry, the Spanish were prepared again and killed a huge number of pirates. The Spanish hid as much of their merchandise as they could, but there were still several warehouses full of valuable silks, cloths and linen left behind.

Morgan seized a beached ship, and ordered his men to set fire to the city’s most important buildings, and the city began to burn. Sources more sympathetic to Morgan argue that the Spanish set fire to their own city to prevent Morgan from taking it, but the end result was the same. Panama City, as it was, was wiped off the map. The modern day city of that name actually sits in a different location from the old one, it was that thoroughly destroyed. When the flames subsided, the pirates searched the ruins for any precious metals, and then did their usual taking and torturing of prisoners, with the usual effectiveness. And in fact, they did it more brutally than ever after the fight which had just happened. They cut off noses, ears and tongues in addition to the eye gouging, face burning and racking we’re already so familiar with. They targeted religious people more than anyone else, and Morgan’s raping and drinking, usually more discrete than that of his men, became the most flamboyant of all. And after a few weeks, he and his men were ready to head back to their ships. They marched with dozens of prisoners both for ransom and to deter attacks, as well as to help carry the treasure.

On the way back, though, Morgan ordered his men to swear that they hadn’t taken anything for themselves that wasn’t disclosed to the group, and commanded that each of his surviving men, himself included, be searched thoroughly to make sure that not so much as a sixpence had been concealed from the group. This wasn’t standard procedure, and it especially infuriated the French, who already had a tense relationship with their English colleagues.

As the last part of their raid, Morgan sent a ship to order Porto Bello to pay a ransom for the Chagres Fort, and Porto Bello said he could do whatever he wanted because they wouldn’t give the pirates so much as a farthing. So, Morgan destroyed the fort.

The big problem came, though, when it was time to divide the spoils. Morgan’s men had gotten the bulk of the valuables in one of Spain’s wealthiest cities, and a majority of them had been killed, which should have meant that survivors ended up with even more extravagant amounts of wealth.

Instead, they ended up with just 200 pieces of eight each. All that work for about 50 pounds sterling. The English complained, and Morgan ignored them, but the French started preparing a mutiny. And in response to this news, Morgan loaded his own ship with the really valuable stuff, and snuck away without warning anyone but his closest companions. He left the rest, including all the French, without so much as the food necessary to sustain them on their return to Jamaica or Tortuga.

According to a legend which persists on Providence Island to this day, Morgan stopped there on his way back to Jamaica to hide the treasure from that ship. And frankly, the reports of his return to Jamaica don’t include the kind of over the top wealth that he had taken. It would also have been extremely difficult to find treasure on that island if it were hidden by someone familiar with its geography, which Morgan was. All that to say, well we all like to believe those stories, right? And it’s certainly possible.

When Morgan returned to Jamaica, Modiford’s council gave him a formal vote of thanks, but things were about to change. After Morgan’s defeat of the Spanish fleet at Maracaibo, the Spanish king had protested to Charles II and demanded a new peace treaty. This treaty explicitly stated that neither country’s ships could appear in the other’s ports without explicit permission. There could be no piracy, because English ships would not be allowed anywhere near Spanish ports unless the Spanish invited them. And if one did, Spain had the right to assume it was a pirate ship and attack. And this wasn’t just an idle threat. They fully intended to do this, and when the treaty was signed, they did. They sank every English ship in Spanish waters without permission, and slaughtering crews assuming they were pirates.

All of this had happened after Maracaibo, and news of the treaty arrived in Jamaica, along with explicit orders that Morgan stop his piracy just a couple days after Morgan had left for Cartagena. That timing was suspiciously convenient, and Modiford could have intercepted Morgan’s men at either Cartagena, or Providence Island, or even Panama, to tell him the attack was off, and yet he hadn’t. All this to say that, months after England and Spain signed a treaty which explicitly forbade privateering, Henry Morgan had wiped one of the biggest cities in Spanish America off the map with Modiford’s permission. And he returned to an official commendation from the governor, even though the governor knew full well the attack had been wholly illegal.

And this could not be ignored. So soon after Morgan returned to Jamaica, Thomas Lynch arrived in the colony with orders to replace Modiford as governor, to send both him and Morgan back to England to stand trial, and to put a stop to buccaneering no matter what it took. And Lynch was dedicated to his mission. He had actually been in Jamaica before as part of Cromwell’s Western Design, and he’d remained on the island. Modiford’s corruption had pushed him to leave, and he’d been vocal about his disapproval of the governor. So now, Lynch saw in his orders from Charles II a chance to return Jamaica to its original course. No piracy, just agriculture and industry, a new and greater Barbados.

Morgan’s men, though, had been sending hundreds of thousands or even millions of pounds through what had previously been the most horrifically awful place in English America. He had recruited the people who had gotten the short end of the stick, and given them lives they couldn’t have dreamed of. Yes, there was excess and debauchery and unimaginable amounts of cruelty, but besides the fact that some people enjoyed that, the result of this was that Jamaica had been transformed. There was money to be made, not just in piracy, but in catering to pirate whims and appetites. Bars, inns, brothels, all could yield a healthy income. People with a little bit of foresight and the ability to look the other way could build comfortable lives. And under Modiford, Jamaica had actively catered to and built itself up for this type of person. Modiford had also led by example in using some of the money to build up new industries and a diverse economy, not just sugar but also salt, cocoa and pimento.

And for Thomas Lynch, all of that meant that the colony’s population had absolutely no interest in cooperating with him or returning to his vision.

Lynch granted pirates sugar plantations and high salary positions in the Royal Navy to entice them away from a life of plunder. He offered them full pardon and indemnity as long as they cooperated with him and stopped buccaneering. But people refused. Turning away from pirate adventures and toward sugar planting wasn’t as appealing a prospect as he’d hoped. Neither was turning from plunder to salaried work. Desperation and ideology may have motivated some pirates, but again, lifestyle and money kept them in that line of work. There were some pirates who plundered a couple times and used the money to go build reputable lives, but they were very few, and very far between. Lynch was offering them something they could have bought after one successful raid, but chose not to. And their decision hadn’t changed.

In one 1672 example Lynch’s thwarted efforts, Lynch had ordered the trial of a pirate who had taken a Spanish ship and murdered its crew, but Thomas Modiford’s son told the Jury not to convict him. The pirate was released, and within an hour he was drinking with his own jury at the bar. Lynch had him re-arrested, though this was itself illegal, and after a second trial he was hanged, but his death was “as much regretted as if he had been as pious and innocent as one of the primitive martyrs.” Lynch tried to explain to Jamaicans that the English should fear the French, who were actually engaged in privateering against the English at this point, rather than the Spanish, but no one listened. At one point, he found the governor and bishop of Santa Marta, in modern Colombia, who had been taken prisoner and brought to Jamaica, and he returned them to their home.

Nor would Jamaicans allow Lynch to arrest Modiford or Morgan. He ended up having to trick both of them in different ways. He invited Modiford on board a ship for a dinner party, and arrested him there, while he effectively carried Morgan out of bed in the middle of the night.

And Lynch would ultimately fail to tame Jamaica. He did send Modiford and Morgan back to England, and they spent three years in the Tower of London to placate Spain, but even in there they lived well and were treated like celebrities. And when they were released, in 1675, they were invited to court, given commendations, and given new positions in Jamaica, including Morgan replacing Lynch as leader of Jamaica. He took the role of acting governor, if only temporarily, as well as the head of the court of vice admiralty. Ironically, this put him in charge of hanging many of the men who had previously served under him but refused to turn away from piracy, but he did so with no hesitation. Meanwhile, Modiford became head of the colony’s courts. Both remained incredibly popular, and any governor who opposed either of them found himself ostracized, though none as much as Lynch.

Both lived as heroes and leaders of the colony until their deaths, which were deeply mourned. Modiford died in 1679, and his tombstone called him “the soul and life of all Jamaica, who first made it what it now is … the best and longest governor, the most considerable planter, the ablest and most upright judge this island ever enjoyed.” Morgan’s probably read similarly, but four years after his 1688 death, his grave was washed into the sea by a hurricane, along with the majority of Port Royal.

And like I said, the two together had effectively shaped Jamaican society. When we started this series, Jamaica was little more than a place where Irish people were sent to die. No one wanted to live there, and the people who dared try faced a death rate even higher than Virginia’s. Morgan’s plunder had brought the money needed to change that, with millions of pounds worth of plunder flowing through Port Royal to the rest of the colony on a regular basis. And Modiford had encouraged it.

For people who wanted to use this wealth to make a more legitimate living, piracy still gave them a leg up on places like Barbados. Charles II never passed import or export duties on Jamaica, no 4.5%, no tax on liquor, nothing more than quit rents. So Jamaican sugar could be sold cheaper and for a greater profit than that of Barbados or the Leewards. The Navigation Acts were impossible to enforce there, and even when a later governor noted the avoidance of these and English mercantile policy as a motivation for piracy, the English government refused to do anything about it. And at the same time, its ports became one of the principal slave trading centers of the Western world, creating yet another income stream. Thanks to all of this, Jamaica started to overtake Barbados as England’s wealthiest colony.

And that brings us to the end of our Restoration Caribbean series. Barbados and Jamaica were two radically different colonies which followed radically different paths, and which impacted the development of America as a whole in radically different ways. And next episode, we will start to see some of that American impact in our discussion of the founding of the colony of Carolina.