Background

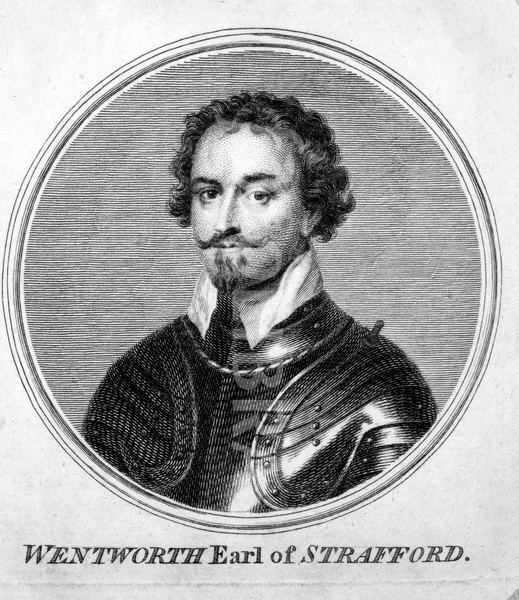

On May 12, 1641, Thomas Wentworth, the Earl of Strafford was executed. It was a pivotal moment in the relationship between King Charles and the Parliament he would soon be at war with.

This may not strictly speaking be American history, but it’s very connected to the history we’re discussing right now, and though it’s a speech I love, it’s not one that’s shared often. So, I thought it was worth posting here. Strafford also made a brief appearance in the Virginia Company episodes of the Jamestown Series.

One of Charles I’s closest advisers, Strafford became a scapegoat for much of the country’s strife. He was appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland, but when he returned to England at Charles’s request during the Bishop’s War, Parliament immediately moved to impeach him. Strafford and John Pym had been acquaintances (and mostly enemies) since attending college together, and they found themselves leading rival factions in the years before the English Civil War.

Pym was the leader of the Parliamentary movement until his death. Strafford was an Anglican from an old Yorkshire family, and fundamentally a royalist, though one who wanted to see a balance between king and parliament. He’d always favored law over ideology, and never forged long-term political alliances with people more ideological than himself. In terms of personality, he was known for his personal warmth, but professional ambition and ruthlessness.

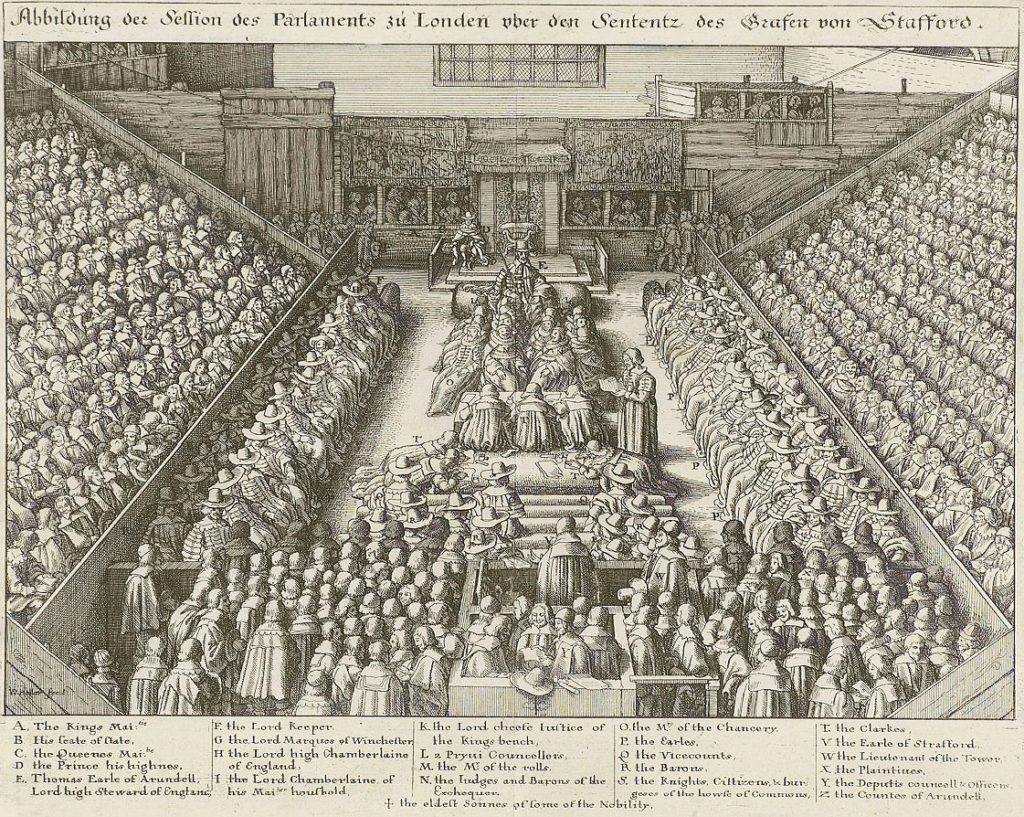

When Strafford returned to England at Charles’s request, Pym and his allies struck hard and fast, accusing him of treason. When they couldn’t convict him (the charge was ridiculous), they wrote a bill of attainder – effectively declaring him a traitor by an act of Parliament. Charles said he’d never sign the bill, but Parliament threatened his wife (a Catholic).

Then, the House of Lords passed the bill by a vote of 37-11, seemingly not because they believed it was right, but because they believed the king would reject it and take the political fallout himself.

And there was political fallout for MPs and Lords who voted against it. George Digby, son of the Earl of Bristol, a long-term enemy of Strafford who had helped the trial against him, now led the charge against the bill of attainder, concluding by saying:

I doe before God discharge myself to the utmost of my power: and with a clear conscience wash my hands of this man’s blood, by this solemn protestation. That my vote goes not to the taking of the Earl of Strafford’s life.

Printing copies of Digby’s speech was declared slanderous to Parliament, and existing copies were ordered to be publicly burned. Strafford’s opponents then petitioned Charles to confer no honor or employment on Digby, who found himself assaulted by mobs accusing him of apostasy, and calling him Strafford’s “false son.” In fact, his name was only cleared from the growing furor when the text of his speech was printed.

Then, someone printed a list of everyone who had voted against the bill of attainder and posted it around London under the title “Enemies of Justice and Straffordians,” and hinting that they should perish with Strafford.

In little over a year, the country would be in a civil war, and the situation reflected that.

Charles wavered, and only signed after Strafford, himself, sent the king a message telling him to do what he needed to for the good of the country. After signing the bill, he sent his son (the future Charles II) to Parliament to ask that the sentence be commuted to life in prison (which would still mean that Strafford had no influence in politics, and the king’s own power was diminished, so Parliament would retain all benefits it got from the trial). Parliament refused. The prince then asked for one day’s delay in the execution, but Parliament again refused.

Charles never forgave himself for allowing the execution.

Context

With the king behind him and no legal justification for the charges against him, Strafford had remained confident through his trial and most of the political battle afterward. It was only the day before his execution that he learned that he would be executed.

Strafford spent the day writing letters to his family, friends and servants, and visited Laud’s cell in the Tower. He asked the Lieutenant of the Tower for permission to see Laud and exchange a few parting words, but the Lieutenant refused, saying he would need to ask Parliament for that favor. When Strafford pointed out that the Lieutenant would hear every word, and that “this is not a time for me to plot treason, or him to plot heresy,” the response was still that he would have to petition Parliament.

“No. I have gotten my dispatch from them, and will trouble them no more. I am now petitioning a higher court, where neither partiality can be expected nor error feared.” Then he turned to the Archbishop of Amagh, and said, “But, my Lord, what I would have spoken to his Grace is this: You shall desire the Archbishop to lend me his prayers this night, and to give me his blessing when I go abroad tomorrow, and to be in his window, that by this my last farewell, I may give him thanks for this and all his former favors.”

Amagh gave Laud the message, and returned with his reply. Laud said he would do the first in conscience, and the second in duty and obligation, but that he wasn’t sure he could bear to do the last.

The next morning, as London’s streets filled with people of all ranks hoping to watch the execution, and before Strafford left the Tower, he gave this speech. It’s a speech full of warnings which are even more meaningful in retrospect. It’s pointed, it’s penitent, and I think it’s pretty amazing.

He also gave a speech on the scaffold, itself, which I’ve put in another post.

I’ve edited these very, very slightly to make the language more modern and readable in parts, but here’s a link to the original text.

Strafford’s speech to the Lords in the Tower

Right honorable, and the rest, you are now come to convey me to my death.

I am willing to die, which is a thing no more than all our predecessors have done, and a debt that our posterity must in their due time discharge, which since it can be no way avoided, it ought the less to be feared. For that which is common to all, ought not to be intolerable to any. It is the law of nature, the tribute of the flesh, remedy from all worldly cares and troubles, and to the truly penitent, a perfect path to blessedness.

And there is but one death, though several ways unto it. Mine is not natural, but enforced by the law and justice. It hath been said that laws vex only the meaner sort of people, but the mighty are able to defend themselves.

It is not so with me, for to the law I submit myself, and confess that I receive nothing but justice — for he that politically intends the common wellbeing may be called a just man, but he that practices either for his own profit, or any other sinister ends, may be well termed a delinquent — neither is delay in punishment any privilege or pardon. And moreover, I ingenuously confess with Cicero, that the death of the bad is the safety of the good that be alive.

Let no man trust either in the favor of his prince, or the friendship and kinship of his peers, and much less in his own wisdom and knowledge, in which I ingenuously confess I have been too confident.

Kings, as they are men before God, are also gods before men, and I may say with a great man once in this kingdom, had I striven to obey my God as faithfully as I fought to honor my king diligently, I would have stood and not fallen. Most happy and fortunate is that prince, who is as much for his justice feared, as for his goodness beloved. For the greater that princes are in power above others, the more they ought in virtue to excel others; and such is the royal sovereign whom I late served.

As for my peers, the correspondence that I had with them during my prosperity was to me very delightful and pleasing, and here they have commiserated my ruin. I have plentifully found, for the most generous of them, I may boldly say, that though they have detested the fact, yet they have pitied the person delinquent. The first in their loyalty, the last in their charity, ingenuously claiming that no subject or peer of my rank has ever had the help of the council, the benefit of time, or a more free and legal trial than I have had, and that none of my predecessors had so much favor from his prince, so much sufferance from the people (which I comprehend as the understanding commons, not the many headed monster, the multitude). But I have offended, am sentenced, and must now suffer.

And as for my too-much-confidence in my supposed wisdom and knowledge, therein have been the most deceived. For he is wife to himself, that knows by others’ faults to correct his own offences. To be truly wife is to be secretaries to ourselves, for it is mere folly to reveal our intimate thoughts to strangers.

Wisdom is the most precious gem with which the mind can be adorned, and learning the most famous thing for which a man ought to be esteemed, and true wisdom teaches us to do well, as to speak well: in the first I have failed, for the wisdom of man is foolishness with God.

As for knowledge, it is a thing indifferent both to good and evil, but the best knowledge is for a man to know himself. He that doth so shall esteem of himself but little, for he considers from whence he came, and whereto he must go, he regardeth not the vain pleasures of this life. He exalts God, and strives to live in his fear.

But he that knows not himself is willful in his own ways, unprofitable in his life, unfortunate in his death, and so am I. But the reason why I sought to attain unto it was this: I have read that he that knows not that which he ought to know, is a bruit beast among men, and he that knows more than he ought to know, is a man among beasts. But, he that knows all that may be known, is a god amongst men. To this I much aspired, in this I much failed. Vanity of vanities, all is but vanity.

I have heard the people clamor and cry out, saying that through my occasion the times are bad. I wish that when I am dead they may prove better. Most true that is, that there is at this time a great storm impending (God in his mercy avert it.) And since it is my particular lot, like Jonah, to be cast into the sea, I shall think my life well spent to appease God’s wrath, and satisfy the people’s malice.

Oh what is eloquence more than ayre? Fashioned with an articulate and distinctive sound, when it is a special virtue to speak little and well, and silence is oft the best oratory. For fools in their dumbness may be accounted wise. It (eloquence) hath power to make a good matter seem bad, and a bad cause appear good, but mine was to me unprofitable, and like the Cypress trees — which are great and tall, but altogether without fruit.

What is honor but the first step to disquietness? And power is still waited on by envy, neither hath it (honor) any privilege against infamy. It is held to be the chief part of honor for a man to join to his office with courtesy and affability, commiseration and pity, for thereby he draws to himself, with a kind of compassion, the hearts of the multitude.

But that was the least part of my study, which now makes me call to mind, that the greater the persons are in authority, the sooner they are caught in any delinquency, and their smallest crimes are thought to be capital. The smallest spot seems great in the finest linen, and the least flaw is soonest found in the richest diamond. But high and noble spirits, finding themselves wounded, grieve not so much at their own pain and perplexity as at the derision and scoffs of their enemy. But, for my own part, though I might have had many in life, I hope to find none in my death.

Amongst other things which pollute and contaminate the minds of great spirits, there is none more heinous than ambition, which is seldom unaccompanied with avarice. Such, to possess their ends, care not to violate the laws of religion and reason, or to break the bonds of modesty and equity with the nearest ties of kinship and amity, of which as I have been guilty, so I crave at God’s hands forgiveness. It is a maxim in philosophy that ambitious men can never be good counselors to princes. The desire of having more is common to great lords and a desire of rule a great cause of their ruin.

My lords, I am now the hopeless precedent. May I be to you all a happy example, for ambition devours gold and drinks blood, and climbs so high by other men’s heads, that in the fall it breaks its own neck. Therefore, it is better to live in humble content, than in high care and trouble, for more precious is want with honesty, than wealth with infamy. For what are we but mere vapors, which in a serene element ascend high, and upon an instant, like smoke vanish into nothing? Or, like ships without pilots, tossed up and down upon the seas by contrary winds and tempests? But the good husbandman thinks better of those ears of corn which bow down and grow crooked, than those which are straight and upright, because he is assured to find more store of grain in the one than in the other. This all men know, yet of this how few make use. The defect whereof must now my pain, my suffering prove to others profit.

For what hath now the favor of my prince, the familiarity with my peers, the volubility of a tongue, the strength of my memory, my learning or knowledge, my honors or offices, my power and potency, my riches and treasure (all these the special gifts, both of nature and fortune) what have all these profited me? Blessings I acknowledge, though by God bestowed upon man, yet not all of them together upon many. Yet by divine providence, the most of them met in me, of which, had I made happy use, I might still have flourished who now am forced immaturely to fall.

I now could wish, (but that utinam is too late) that God with his outward goodness towards me had so commixed his inward grace, that I had chosen the medium path, neither inclining to the right hand nor deviating to the left. But like Icarus with my waxen wings, fearing by too low a flight to moisten them with the waves, I soared too high and too near the sun, by which they being melted. I aiming at the highest, am precipitated to the lowest and am made a wretched prey to the waters. But I, who before built my house upon the sand, have now settled my hopes upon the Rock, my Savior, by whose only merits my sole trust is, that whatsoever becomes of my body, yet in His bosom my soul may be sanctuaried.

Nimrod would have built a tower to reach up to heaven and called it Babel, but God turned it to the confusion of languages, and dissipation of the people. Pharaoh kept the children of Israel in bondage and, having freed them, in his great pride would have made them his prey, but God gave them a dry and miraculous passage, and Pharaoh and his host a watery sepulcher. Balthazar feasted his princes and prostitutes, who drunk healths in the vessels taken from the temple, but the hand of God writ upon the wall, Men, Tekel, Phoras, and that night before morning was both his kingdom and life taken from him.

Thus God lets men go on a great while in their own devices, but in the ends it proves their own ruin and destruction. Never suffering them to effect their own ruin and destruction, never suffering them to effect their desired purposes. Therefore, let none presume upon his own power, glory, in his greatness, or be too confident in his riches. These things were written for our instruction, of which the living may make use, the dying cannot, but wit and unfruitful wisdom are the next neighbors to folly.

There can be no greater vanity in the world than to esteem the world, which regards no man, and to make slight account of God, who greatly respects all men. And there can be no greater folly in man than by much work to increase his goods, and pamper his body, and in the interim with vain delights and pleasures to lose his soul. It is a great folly in any man to attempt a bad beginning in hope of good ending, and to make that proper to one, which was before common, and is mere indiscretion and the beginning of discord, and which I positively wish may end in this my punishment.

Oh how small a proportion of earth will contain my body, when my high mind could not be confined within the spacious compass of two kingdoms? But my hour draws on, and I conclude with the Psalmist, not aiming at any one man in particular, but speaking for all in general: How long will you judges be corrupted? How long will you cease to give true Judgement? Blessed is the man that does not walk in the council of the wicked, nor stand in the way of sinners, nor sit in the seat of the scornful, therefore they shall not stand in the Judgment nor sinners in the assembly of the righteous.